Wenwen Tian and Stephen Louw

An important part of training to become a teacher is the opportunity to get practical teaching experience. For this reason, training programmes often include a teaching practice component in which trainee teachers teach real students under supervision of a trainer. Understandably, these teaching practice lessons can be highly stressful for trainees, and because they are still learning to teach, trainees may make mistakes or get flustered as the lessons progress. Following the lesson, the trainer conducts a feedback conference with the trainee. In this conference, trainers traditionally focus on aspects of the lesson which did not go well in an attempt to help trainees identify areas where they can improve. This focus on the deficits of lessons, however, risks ignoring the trainee’s emotional wellbeing.

One way around the problem is to find ways for trainees to identify the strengths they already have. By focusing on strengths instead of weaknesses, trainee teachers can work on strengthening their lessons without the possibility of losing heart because of their failures. This is the basis of a strengths-based mentoring approach.

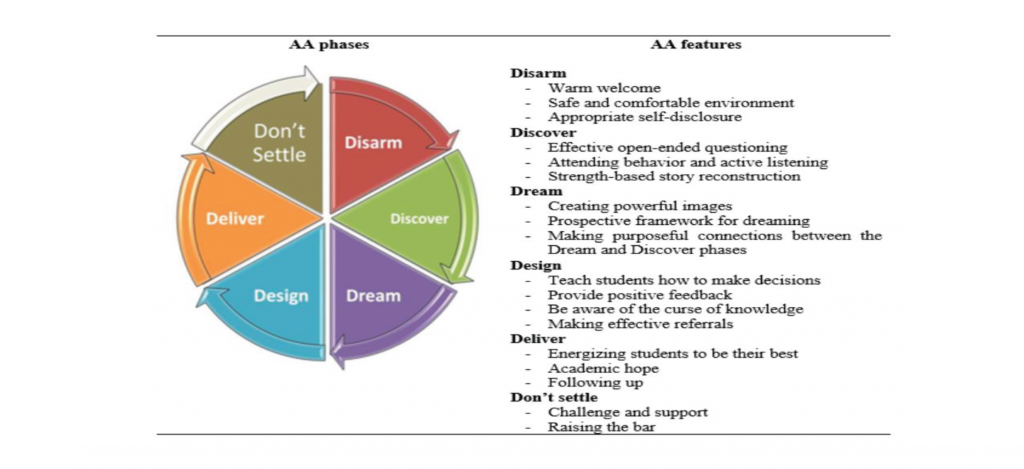

Our research explored one such strengths-based mentoring approach, called Appreciative Advising (AA). In AA, the trainer moves through a series of phases and features (see Figure 1) to help a learner identify strengths and build on them develop themselves. Much of the research so far has focused on the use of AA in the supervision of graduate students. A supervisor in a graduate programme typically has a year, and often longer, to help a student identify their strengths and utilize them to build a successful academic career. We wondered whether AA would work in a teacher training programme where the supervisor has access to a trainee for only 4 weeks.

We asked a trainer working on a 4-week intensive language teacher training course to keep a reflective journal while he implemented AA with his trainee teachers. We were particularly interested in how he implemented AA in the feedback conferences following teaching practice. Following his implementation of AA over three separate groups of trainees, we interviewed him to find out more about his experience in implementing AA.

Figure 1. AA phases and features

Adapted from Bloom, Hutson, and He (2008)

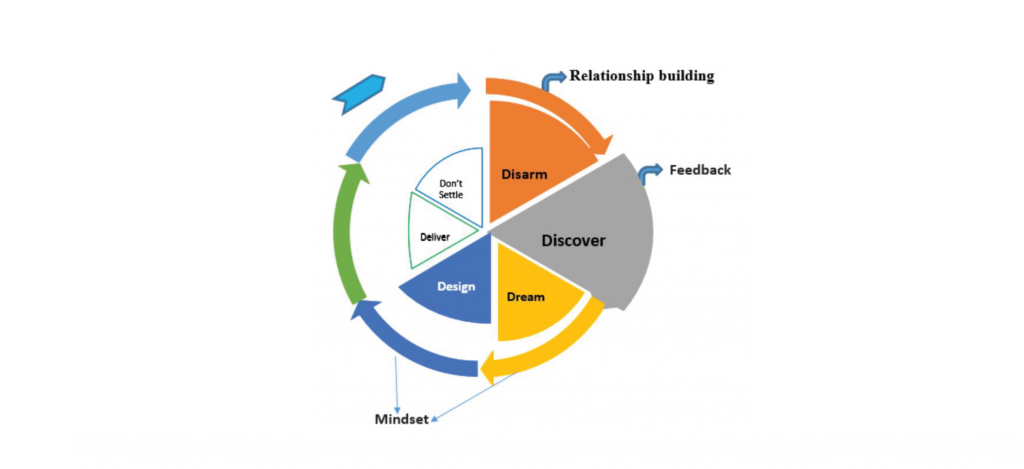

In our analysis, we specifically tried to identify which AA phases and features the trainer included in his meetings with the trainees. To do so, we analysed the journals and interview transcript quantitatively for keywords using a corpus-based approach. This told us the sorts of words and phrases that were common in the trainer’s reflections on AA and how he interpreted and implemented these phases in the context of the feedback conference. The keyword analysis showed us that the trainer was able to incorporate many elements from AA, but not the final two stages: ‘Deliver’ and ‘Don’t settle’. Figure 2 summarizes how the data from the trainer was matched to the six AA phases.

Figure 2. Associating identified themes with AA phases

To find out why these two stages were missing, we examined the data qualitatively using thematic analysis. This analysis highlighted a variety of challenges the trainer faced in implementing the full six phases of AA. For instance, because the trainee teachers only study for four weeks, the trainer met some trainees only once. That meant he was unable to follow through with the full AA cycle even if he could set up the initial phases successfully. In spite of the challenges, however, the data showed that the trainer was positive about the implementation of AA, and was confident that his utilization of the approach was beneficial for the trainee teachers. This study helps build on our understanding of the benefits of using a strengths-based approach in working with trainee teachers, even in very short teacher training programmes.

This article is based on: Wenwen Tian & Stephen Louw (2020). It’s a win-win situation: Implementing appreciative advising in a pre-service teacher training programme, Reflective Practice, 21(3), 384-399. DOI: 10.1080/14623943.2020.1752167